Personality Theory

A Brief Survey of the Field Today and Some Possible Future Directions

Robert E. Beneckson

The scientific study of personality as a focus within the larger field of psychology must begin with a definition of the term itself. The origin of the term lies in the Latin word, persona, generally understood as the mask that people wear in dealing with others as they play various roles in life. Although there are various definitions psychologists use for the term personality, a consensus definition involves recognition that we are concerned with studying a pattern of a number of human tendencies, including traits, dispositions, unconscious dynamics, learned coping strategies, habitual and spontaneous affective responses, goal-directedness, information-processing style, and genetic and biological factors that give some degree of consistency to human behavior. Very important in this approach to understanding personality are the notions of both a pattern of characteristics and the relatively consistent nature of their occurrence. Personality theory is not greatly concerned with a unique occurrence of a particular behavior, but rather the consistent pattern of behaviors, cognitions, and emotions and their overlapping and unique manifestations in individuals.

At this point in the development of a science of personality there is no general agreement on all the factors which contribute to, and make up human personality. There is not even general agreement over which aspects to study or exactly how to study them. Nevertheless, the field of personality theory and research is exceedingly rich and varied. However, we must approach this richness by understanding the approaches of various theories and their particular focus. By the time we conclude our examination of the current theories we may be able to attempt some level of integration of these approaches.

Although various textbooks separate personality theories into clusters linked by common themes for study (psychodynamic, learning theory based, trait and factor and humanistic approaches are common ways of providing a classification system. This paper will use a slightly modified version of the classification system of Friedman and Schustach (Friedman & Schustach, 2003). We can organize personality theories in to eight groups. They are: 1) Psychoanalytic, 2) Neo-Analytic/Ego, 3) Biological/Evolutionary, 4) Behavioral, 5) Cognitive, 6) Trait, 7) Humanistic/Existential, and 8) Interactionist. We will discuss each group of theories in enough detail for clear understanding of the basics, but not comprehensively, as this would require another textbook.

Psychoanalytic Theory

Psychoanalytic personality theory is based on the writings of the Austrian Physician Sigmund Freud. Developed in the late Victorian period, Freud’s ideas were quite radical in their time. Freud created two basic models of the workings of the human mind. The first emphasized levels of consciousness and was known as the topographic model. The second model approached human personality by exploring the interaction between the three parts of the mind Freud identified (the well-known id, ego, and super-ego). This was known as the structural model. Later these were combined so that personality was conceptualized as resulting from the dynamic interplay between levels of consciousness and particular structures.

In Freud’s thinking, the id represents our basic primitive drives, principally sexual and aggressive in nature. The ego is that aspect of personality which is capable of reason and self-control and helps the individual to adapt to the demands of the external world. In order to do this, the ego must gain control of id desires and channel them in socially acceptable ways. Left to its own devices, the id would be seeking immediate gratification of the drives for pleasure and aggression that Freud believed were the basic motivations for human beings on this level. So, the ego must step in and guide our behavior in a realistic manner in order to find ways of satisfying the demands of the id without causing social difficulty for the person. The third structure of the mind, the superego, develops out of this struggle and helps guide our behavior according to the norms of our culture. The three mental structures must work in some degree of harmonious balance for a person to be functioning in a healthy manner, i.e. satisfying their basic pleasure drive in accord with reality, and in a socially acceptable manner. In terms of levels of consciousness, the ego lies in the domain of the conscious and preconscious levels of awareness, the superego can be conscious, preconscious, or unconscious, and the id is unconscious. Freud compared the levels of mental functioning to an iceberg with the smallest part (the conscious mind) above the water line and the rest below it, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

In addition to this conception of the mind’s functioning and the basic motivations of human behavior, Freud shocked the society of his time by tracing the development of the sexual drive (in his thinking more a drive for various sensual pleasures and not merely the sexual drive) all the way back to birth and suggested that this sexual drive developed in various stages so that various physical zones (erogenous zones) were the primary focus of pleasurable stimuli and attention at various ages. These developmental phases are his well-known oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital periods.

Because Freud viewed the id as the strongest aspect of

personality and the ego as a rather weak aspect, continually under stress by

constantly having to mediate between the inner demands of the id and the

demands of external reality as well as the super-ego’s often overly critical

and moralistic judgments against oneself, the ego develops defense mechanisms

to deal with anxiety and stress brought on from the inner struggle with the id

and superego.

This extremely condensed discussion of Freud’s theories should provide a basic understanding of the psychoanalytic view of personality functioning. Each person strikes different balances between the id, ego, and super-ego. They cope with their drives and desires differently and all have different ideas about what is acceptable behavior (the content of the superego). People have different methods of ego defense and adaptation to the necessary frustration of the desire for immediate gratification. The study of the dynamics between the structures and levels of consciousness of the person is what informs the psychoanalytic, and more broadly, the psychodynamic view of personality.

Neo-Analytic/Ego Psychology

The Neo-Analytic school usually includes such theorists as Carl Jung, Alfred Adler, Karen Horney, and Erik Erikson. Others could be included, but we are more interested in the basic contributions to personality theory of this school rather than a comprehensive listing of theorists. Essentially this school of thought is an attempt to extend and modernize the theories of Freud. Ego psychologists believe that the ego is present at birth and has its own independent energy source, contrary to Freud, who believed that the ego was a relatively weak structure that “captured” its energy from the id. While neo-analytic thinkers acknowledge the role of the unconscious in influencing behavior, their focus of study is more on the conscious self as a person develops and grows, and has to interact both with the demands of external reality and inner struggles with emotions, and drives, and desires.

The ego has various functions and abilities, such as cognition, drive delay, memory, and other adaptive functions (like learning). Many of the phenomena studied by experimental psychologists, such as memory and learning, belong to the province of the ego as understood from the ego analytic point of view.

Personality is formed from the progression of the ego through various stages of development highlighted by a basic conflict that yields positive outcomes if successfully mastered, or personality problems if unsuccessfully mastered. The following table illustrates these stages as described by Erikson.

|

|

Erik Erikson's 8 Stages of Psychosocial Development |

Summary Chart

Table 1

|

Stage |

Ages |

Basic |

Important |

Summary |

|

Birth to |

Trust vs. Mistrust |

Feeding |

The infant must form a first loving, trusting relationship

with the caregiver, or develop a sense of mistrust. |

|

|

18 months |

Autonomy vs. |

Toilet |

The child's energies are directed toward the development

of physical skills, including walking, grasping, and rectal sphincter

control. The child learns control but may develop shame and doubt if not handled

well. |

|

|

3 to 6 years |

Initiative vs. |

|

The child continues to become more assertive and to take more

initiative, but may be too forceful, leading to guilt feelings. |

|

|

6 to 12 years |

Industry vs. Inferiority |

School |

The child must deal with demands to learn new skills or

risk a sense of inferiority, failure and incompetence. |

|

|

12 to 18 years |

Identity vs. |

Peer relationships |

The teenager must achieve a sense of identity in

occupation, sex roles, politics, and religion. |

|

|

19 to 40 years |

Intimacy vs. |

Love relationships |

The young adult must develop intimate relationships or

suffer feelings of isolation. |

|

|

40 to 65 years |

Generativity vs. Stagnation |

Parenting |

Each adult must find some way to satisfy and support the

next generation. |

|

|

65 to death |

Ego Integrity vs. Despair |

Reflection on and acceptance of one's life |

The culmination is a sense of oneself as one is and of

feeling fulfilled. |

Although differences of emphasis exist between thinkers in the Neo-Analytic school, the concept of a strong and adaptive ego able to cope in a flexible manner with different situations, rather than an id driven person whose behavior is determined heavily by unconscious forces, is a unifying tenet of these thinkers.

Biological/Evolutionary

This school interprets behavior and personality as a function of our genes, brain structure, physiology, and evolution. The concept of the role of genes and evolutionary factors as contributors to personality and behavior can be traced to the writings of Charles Darwin. The idea is that is person is unique and determined by combinations of genetic factors passed down from one’s ancestors. Human traits and behaviors are a result of natural selection. Those traits which contribute to survival value have persisted and been passed from one generation to the next. This is known as evolutionary personality theory. One major difficulty is knowing the selection factors which have shaped any particular human trait, and not falling in to circular reasoning, i.e., concluding that any trait or behavior that exists today must have had survival value in the past or it would have been bred out of the species.

The human genome project, which has recently succeeded in mapping the structure of human genes, has a great deal of potential for the field of biological personality theory. While the structure of human genes is now known, the functions and interaction effects that may result in specific human personality traits and behaviors is not known. The study of these factors is known as behavioral genomics.

There are other approaches within the field which have yielded more concrete results. One is what is referred to as temperament theory. This is the idea that each person has some stable differences in how their nervous system processes stimuli and is demonstrated by differences in emotional reactivity. We can see examples of this in babies who differ markedly on factors like activity levels, amount of crying, responses to cuddling, and sleep patterns. These appear to be examples of inborn temperament and biologically determined.

There is general agreement on four basic aspects of temperament. 1) The activity dimension which is shown by differences on a continuum in children from extreme activity to extreme passivity, 2) The emotionality dimension which involves a continuum from ease of arousal of emotions like anger or fear, to a calmer and more stable emotionality at the other end of the scale, 3) The sociability dimension which involves ease of approaching others on one end of the scale, and withdrawal from human contact on the other, and 4) The aggressive/impulsive dimension which involves aggressive and cold behavior on one end, and conscientiousness and friendliness on the other. The point here is that these characteristics are seen as very strongly biologically determined and not the result of childhood experiences as a Freudian, for example, might view them.

A more detailed survey of the field would include other research and theory that attempts to link specific traits to physiological factors and specific brain structures. One example of this work is the research and theory of H. J. Eysenck. He believes that traits like extraversion-introversion are related to different innate levels of Central Nervous System arousal and activity levels, particularly the reticular activating system of the brain. (Eysenck 1967). Unfortunately, at this time there is little empirical evidence in support of this hypothesis. Another line of research is in the development of psychopathological conditions like schizophrenia. There is very good evidence that people with these disorders show abnormal physiological functioning, although the causes of these dysfunctions are not specifically known as yet. See Figure 2 below, for an example of a brain scan of a schizophrenic vs. a normal brain, and a glucose metabolism study of an obsessive-compulsive patient. These demonstrate some differences between normal and abnormal brains and the presence of a disorder.

Figure 2.

The overall state of biological/evolutionary approaches is that there is certainly evidence for the influence of biological factors in personality development and expression, and in pathological behavior, but the exact nature of these influences is a question for future research.

The behavioral school has its origins in the well-known observations of the Russian physiologist, Ivan Pavlov, that dogs learn to salivate in response to an external event, like the sounding of a buzzer or the ringing of a bell, that previously would have no such effect on the dog’s behavior. The observation of this phenomenon occurred when Pavlov was studying salivation in dogs and led to the formulation of the principles of classical conditioning. What occurs is the pairing of an innate, or unlearned response, with a new external condition, known as a conditioned stimulus. In the case of dogs, the salivary response occurs in the presence of food. When some other external event occurs when the food is presented (like the ringing of a bell), and this pairing happens numerous times, the dog begins to salivate when the bell is rung and no food is present! Thus, the dog has displayed a conditioned response to the bell; he has learned to salivate when no food is presented. This type of learning is known as classical conditioning and is also known as paired-associate learning.

So, the early behavioral school took the position that

behavior could be studied in the laboratory, and that human personality was a

result of learned associations and habits.

The most famous early exponent of behaviorism in

"Give me a dozen healthy infants,

well formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in, and I'll guarantee

to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I

might select - doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief - regardless of his

talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his

ancestors."

He also had some specific advice for raising children, succinctly expressed here.

"Don't kiss and cuddle your children; shake their hands, and then arrange their environments so that the behaviors you desire will be brought under the control of appropriate stimuli."

The

behavioral school continued to develop and found its most well known exponent

from the 1930s, until his death in 1990, in B.F. Skinner. Skinner developed the scientific study of

what he termed operant behavior.

This involved the study of how behaviors that are not innate are learned

in the first place. When a behavior is

followed by a consequence that increases its frequency it is said to have been positively

reinforced.

Skinner developed the concepts of various types of reinforcement to account for this type of learning. Skinner and other behaviorists have devoted a great deal of study to the effects of different types of reinforcement on the acquisition, maintenance, and unlearning of behavior, and have contributed greatly to knowledge of these processes.

The importance of this approach for personality theory lies in the method and philosophy of science of this approach. Behaviorists do not believe that any human activity that is not observable can be studied in a scientific manner. Therefore, personality theories that explain behavior in terms of inner states, such as drive states, or unconscious motivations, or those that posit hypothetical mental structures, such as the ego, the self, etc. are beyond the ability of science to study, and therefore not in the realm of a scientific psychology. Personality, therefore, consists of various learned and observable behaviors both complex and simple, but nevertheless observable and quantifiable.

The behaviorist view of areas of psychology that are generally of interest to personality theorists and researchers takes on a rather different character than other approaches. Two examples will illustrate. Most personality theories view behavior as at least partly motivated by drives and various emotional states. In Skinner’s view, drives are seen as related to the effects of both satiation and deprivation, and therefore they influence the probability of certain behaviors, but they are not the causes of behavior. The view of emotions is similar. Emotions are not the causes of behavior, but are related to contingencies of survival, and contingencies of reinforcement. This approach to explaining human behavior is often called radical behaviorism and in more recent times has been modified by the addition of cognitive elements to the study of behavior, an approach to which we now turn.

Cognitive and Social Learning

The cognitive approach to understanding human personality takes as its starting point the view that people’s perceptions, thoughts, attitudes, expectations, beliefs, and the way they are organized are central to understanding human behavior and personality. Originating with the gestalt psychologists who studied perception in the early part of the 20th century, and utilizing the concept of schemas developed by Jean Piaget, cognitive approaches to personality have continued to broaden and deepen to include social learning theory and modified forms of behaviorism.

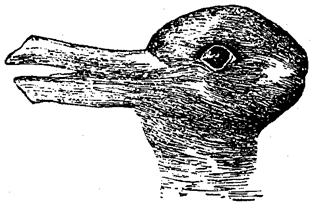

Gestaltists were concerned with the processes by which we organize and interpret our perceptions, and attempted to understand the principles which govern the way human beings organize external stimuli into meaningful patterns. Look at the figure below and decide what you see.

Figure 3.

Is it a duck’s head or a rabbit’s head? The study of the processes which influenced your decision, how you made meaning out of a series of lines and shadows, is the element of gestalt psychology that is the precursor to later more direct explorations of cognitions themselves.

The famous Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget developed the concept of schemas, which are patterns of decoding information and assigning meaning to the world. This happens in stages as children grow, and one set of schemas is modified and replaced by new ones. We know that children (and adults also) have different interpretations of reality as they grow and develop. Schemas are often organized into levels of expectations and attitudes that govern how people expect particular situations to develop, and what behaviors are appropriate for them. This is known as a script. For example, if a new manager in a company behaves in a manner very different from previous management (contrary to the script the workers have learned) there is likely to be considerable dissatisfaction because expectations and the cognitive constructions of the workers have been violated.

As cognitive approaches to personality development have progressed, theoreticians and researchers have studied other cognitive factors that influence behavior. One interesting approach is by George Kelley, and is known as personal construct theory. Kelley believes that, “a person’s processes are channeled by the ways in which he anticipates

events.” We each have our own system of cognitions and mental constructs that we use to predict our own and other’s behavior. This is similar to another cognitive factor called explanatory style. This concept refers to the habitual styles used by people to interpret the events in their lives. Some factors studied include optimism vs. pessimism and learned helplessness.

The application of cognitive factors to behavioral principles was pioneered by Albert Bandura and is known as social-learning theory. Unlike the Skinnerian form of behaviorism discussed previously, Bandura is interested in the inner world of thoughts, and how learning and personality are influenced by it. Bandura sees the self-system, the cognitive processes by which we perceive, regulate, and evaluate our own behavior so that it is effective in achieving our goals and is appropriate to the environment, as central to understanding personality.

Because social-learning theory acknowledges the role of cognition and inner states, it is interested in how previous learning modifies expectancies and knowledge. It recognizes that people learn to anticipate reinforcement and do not have to wait for a tangible external reinforcement. In addition observational learning is possible, the ability for people to learn complex behaviors by watching others perform behaviors without performing them personally and being directly rewarded. This is also known as modeling.

The key element of cognitive research and theory is the influence of what we think on what we do, and combining some of these insights with behavioral learning concepts has extended the explanatory power of both approaches.

Trait

Trait theory goes all the way back to the ancient Greeks, beginning with Hippocrates’s use of the four humors to describe personality. The four humors were bodily fluids and their proportion in the body was believed to be associated with certain personality traits. A sanguine optimistic nature was associated with blood, a melancholic, depressive temperament with black bile, a choleric, angry temperament with yellow bile, and a phlegmatic temperament was associated with slowness and apathy. While today we may view these descriptions as quaint anachronisms, in fact, they are an early attempt to link personality traits to physiological factors, a trend which remains to this day, both in the behavioral genetics field and among some trait theorists who believe that human traits have physiological correlates.

The trait approach, generally, is a descriptive one. We use descriptive language to paint a picture of a person’s style of functioning. Is the person outgoing or reserved, suspicious or trusting, imaginative or practical, controlled or casual? These are some of the dimensions of traits used by Raymond B. Cattell in his famous personality test, “The Sixteen Personality Factors Questionnaire.” The traits he identified in his research are dichotomous and were identified using a statistical method called factor analysis, which is capable of identifying clusters of responses that can separated into specific personality traits. This approach to understanding personality can yield descriptions of human personality on many dimensions, depending on what aspects the researcher is focusing upon.

Since the 1960s and continuing throughout the 1990s, and into this century, trait research and theory has come to the conclusion that personality can be captured on five dimensions, known as the Big Five and explained below.

The Big 5 Factors & Illustrative Adjectives

|

Characteristics

of High Scorers |

Nature of Factor |

Characteristics

of Low Scorers |

|

|

Neuroticism (N) |

|

|

worrying, insecure, emotional, nervous |

Proneness to

psychological distress, excessive carvings or urges, unrealistic ideas |

calm, secure, unemotional, relaxed |

|

|

Extraversion (E) |

|

|

talkative, optimistic, sociable, affectionate |

Capacity for joy,

need for stimulation |

unartistic, conventional |

|

|

Openness (O) |

|

|

creative, original, curious, imaginative |

Toleration for

& exploration of the unfamiliar |

unartistic, conventional |

|

|

Agreeableness

(A) |

|

|

good-natured, trusting, helpful |

One's orientation along

a continuum from compassion to antagonism in thoughts, feelings, and actions |

rude, uncooperative, irritable |

|

|

Conscientiouness

(C) |

|

|

organized, reliable, neat, ambitious |

Individual has degree

of organization, persistence, and motivation in goal-directed behavior |

unreliable, lazy, careless, negligent |

Table 2.

If

one were to take a big five based personality test one would obtain scores on each

of the five factors along with interpretations based on the magnitude of the

score. If the reader would like to take

a big five test there is a free version available on the Internet at this

address: http://cac.psu.edu/~j5j/test/ipipneo1.htm.

When considering the trait approach it is

important to realize that what emerges is a description of a person’s behavior

and personality, not the reasons for the existence of the traits identified, or

an analysis of the dynamic interplay between traits. Other theories deal with these questions, and

broader ones, concerning other human needs.

Humanistic/Existential

The humanistic/existential school of personality theory developed largely as a reaction against the dominant schools of psychology in the first half of the 20th century, psychoanalysis and behaviorism. It has come to be called the “Third Force” within psychology because of this. Humanistic/existential psychologists were influenced by European existential philosophers, like Kierkegaard, Husserl, and Heidegger. The most well known American psychologists associated with this branch of personality theory are Carl Rogers, Abraham Maslow and Rollo May.

Humanistic/existential psychologists take a dim view of Freudian determinism and of behaviorism’s lack of ability to deal with the inner nature of man. For the humanist/existentialist the prime focus on a psychology of humans must acknowledge factors that are specifically human, such as choice, responsibility, freedom, and how humans create meaning in their lives. Human behavior is not seen as determined in some mechanistic way, either by inner psychological forces, schedules of external reinforcement, or genetic endowments, but rather as a result of what we choose and how we create meaning from among those choices.

Understanding and enhancing the development of the individual self is key to developing a healthy personality, and this will emerge in human beings if negative factors in the family or society do not interfere with this inner unfolding of the personality in a unique and healthy direction. This development is known as self-actualization and humanistic personality theorists generally agree that this is the goal of healthy human development. How does this happen? Abraham Maslow believed that human needs can be understood as organized in levels from most basic to the more complex, with self-actualization being the highest need.

If the person’s basic needs are adequately met, things will proceed smoothly and the person will grow towards becoming a self-actualizing person. If lower level needs are not adequately met the person can become stuck at a certain level of need and then their personality may become dominated by the needs of that level. For example if a person is stuck on the level of esteem needs, they will tend to continue to seek out situations and relationships that gratify that need in some way and the focus of much of their motivation will be on that level. The figure below illustrates Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs.

Figure 4

Maslow developed the view that human psychological needs were not dissimilar to the need for essential foods and vitamins for physical health, i.e. if we are deficient in basic psychological needs our personality development becomes stunted and we do not fully develop. Corrective action can be taken in psychotherapy to help the person meet the unmet needs and continue their growth, much like a person can take a vitamin supplement to correct a physical problem based on a vitamin deficiency. Maslow believed that only about 1% of the population becomes self-actualizing, and he set about the task of describing the personality characteristics of self-actualizing people in detail. Here is his list of characteristics of self-actualizers:

1.

Realistically Oriented.

2.

Accept Self and Others for What They Are.

3.

Spontaneity.

4.

Problem-Centered vs. Self-Centered.

5.

Somewhat Detached -- Need Privacy.

6.

Autonomous / Independent.

7.

Appreciate People and Things.

8.

History of Profound / Mystical Experiences

9.

Identify with Humanity.

10.

Intimate Relationships Profound and

Emotional

11.

Democratic Values.

12. Does

not Confuse Means with Ends.

13.

Philosophical Sense of Humor.

14.

Creative.

15.Non-conforming.

16.

Transcend Environment -- Do not Just Cope.

The

existential school, while sharing many of the beliefs of the humanistic

psychologists is not as sanguine about the inner unfolding of human

beings. They believe that it requires

active intention to create this inner unfolding, often referred to as authenticity.

Existential psychologists, like Rollo May, believe

that courage is necessary to face the harsh realities of existence whether in

the realms they term the Umwelt - the

external environment, the Mitwelt - the

realm of interpersonal relations, or the Eigenwelt

- the inner world of stimuli and one’s relation to oneself. Man is thrown into the world against

his will, and must learn how to coexist with nature, and the awareness of his

own death and his own potential for either growth or decay. To be healthy, humans must choose a course of

action that leads to what Erich Fromm called the productive

orientation. This is defined as

working, loving, and reasoning so that work is a creative self-expression and

not merely and end in itself. Loving

encompasses four qualities - care, responsibility, respect, and knowledge,

while reasoning involves clear thinking and the perception of others as they

are, and not as we wish them to be. The

reader may note that these qualities have some overlap with the characteristics

of self-actualizers.

Interactionist

The personality theories we have examined thus far, with the exception of the behavioral perspective, tend to emphasize inner factors as the wellsprings of human personality. The interactionist view takes into account inner factors, but believes the expression of these inner tendencies is modified in interaction with environmental factors. An early expression of this view is seen in Kurt Lewin’s famous formula, B = f (P, E) i.e., behavior is a function of the person and the environment.

The psychiatrist, Harry Stack Sullivan, defined personality as the “the relatively enduring pattern of recurrent interpersonal situations.”(Shustack) Again, the emphasis is on the role of social and situational factors in what is expressed and perceived as human personality. Sullivan was influenced by the sociologist George Herbert Mead, who wrote extensively about what he called as the social self, the idea that our self-perceptions develop from interactions with those around us, particularly parents who often supply self-definitions in the formative early years in the qualities they attribute to us and we tend to internalize.

Another important psychologist in this school of thought is

Henry Murray, often known for the development of the Thematic Apperception

Test.

A more contemporary model of interactionist theory can be found in the work of the psychologist Walter Mischel. Mischel takes what is known as a social-cognitive approach. He is interested in four personality variables, competencies - our skills and knowledge, encoding strategies - our particular style and the schemas we use in processing information, expectancies - what we expect from our own behavior and our anticipations of our performance levels, and plans - what we intend to do. The interaction of these cognitive factors with environmental situations results in the expression of personality, but it is a dynamic concept of personality which is in flux as adaptation to inner and external forces is continuously occurring. The consistency of personality stems from the fact that people develop habitual ways of dealing with events that become the behavioral signatures of their personalities.

Interactionist theory also draws

on social-psychology research, which demonstrates that people do not just

manifest inner personality traits despite the circumstances, but are heavily

influenced by environmental factors. A

famous experiment that illustrates this principle is the work of Stanley Milgram on obedience.

Milgram designed an experiment in which a

subject believed he was administering a series of increasingly powerful

electric shocks to a subject whenever the subject failed to learn a list of

words correctly. Prior to the experiment

a panel of experts, including psychologists and psychiatrists, was asked to

predict what percentage of subjects would administer shocks all the way to 450

volts, which was the highest amount possible.

They predicted that only one or two percent would do so, only the

sadistic personalities. In fact,

sixty-six percent of the subjects complied with the instructions of the

experimenter to continue administering shocks all the way to the highest

level. These were regular

well-functioning people and not sadistic individuals. This classic experiment demonstrated the role

of what

Towards an Integrated Theory

The science of psychology is only 124 years old, and lacks integration of data and views of human personality and behavior in many areas. Instead, we have schools of thought and diverse explanatory schemas such as we have so briefly examined in this paper. It is rather like the story of the blind man and the elephant - whichever aspect of the elephant he perceives through touch, be it the tail, the trunk, or a leg, he mistakes for the whole. Advances will be made in integrating personality theory when we can step back and view the elephant as a whole, and not become overly fixated on one of its body parts. In this section we can make some modest attempts to look at the whole elephant.

One theorist who has made some attempts in this direction is

Dr. C. George Boeree, of

“Even

among our list of consistencies, we can find some "metaconsistencies." Being a visual sort, I like to put things

into graphic form. So here goes:

Figure 5.

What

you see here is "poor me" (or "poor you"), at the center of

enormous forces. At top, we have history, society, and culture, which

influence us primarily through our learning as mediated by our families, peers,

the media, and so on. At the bottom, we have evolution, genetics, and

biology, which influence us by means of our physiology (including

neurotransmitters, hormones, etc.) Some of the specifics most relevant to

psychology are instincts, temperaments, and health. As the nice, thick

arrows indicate, these two mighty forces influence us strongly and

continuously, from conception to death.

There is, of course, nothing simple about these influences. If you will notice the thin arrows (a) and (b). These illustrate some of the more roundabout ways in which biology influences our learning, or society influences our physiology. The arrow labeled (a) might represent an aggressive temperament leading to a violent response to certain media messages that leads to a misunderstanding of those messages. Or (b) might represent being raised with a certain set of nutritional habits that lead to a physiological deficiency in later life. There are endless complexities.

I also put in a number of

little arrows, marked (c). These represent accidental influences,

physiological or experiential. Not everything that happens in our

environment is part of some great historical or evolutionary movement!

Sometimes, stuff just happens. You can be in the wrong place at the wrong

time, or the right place at the right time: Hear some great speaker that

changes the direction of your life away from the traditional path, or have a

cell hit by stray radiation in just the wrong way.

Last, but not least, there's

(d), which represents our own choices. Even if free will ultimately does

not stand up to philosophical or psychological

analysis, we can at least talk

about the idea of self-determination, i.e. the idea that, beyond society and

biology and accident, sometimes my behavior and experience is caused by... me!”

(Boeree)

What

Dr. Boeree is doing here is attempting to represent

the various levels studied by personality theorists and show the complex

interaction of forces impacting any individual at any point in time, and how

the dynamics within each individual interact with those influences. This is a very profitable approach because it

is paying attention to multiple factors impacting on, and being influenced by

the individual. It attempts to view the

whole complex “elephant” and not does not attempt to draw all motivations from

one prime source as the various individual schools of thought often attempt to

do (as in Freud’s libidinal drives, Adler’s striving for superiority, or

Skinner’s operant conditioning, for example).

Another

attempt to represent this complexity is used by this writer in teaching

personality theory and is presented below.

Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The way to understand this diagram is to view the three blue circles as representing the inner structure of personality. It incorporates the Freudian structures of id, ego, and super-ego along with the concepts of conscious, preconscious, and unconscious.

Areas that belong to the conscious level and the ego are the phenomena Freud and the ego-psychologists described, such as rational judgment, the ability to delay gratification of impulses, and other such executive functions. However, the phenomena studied by modern cognitive psychologists, social psychologists, and experimental psychologists also belong to this level. Things like perception, attitudes, interpretive schemas, personal constructs, aspects of the self-concept etc., belong to this level of personality.

Aspects of the inner personality that serve as guiding principles that are concerned with morality and ethics and that deal with the ideals one holds for oneself, belong to both conscious, pre-conscious, and unconscious aspects of the super-ego. This would include the self-concept and self-evaluation that humanistic psychologists like Carl Rogers were very concerned with, as well as self-talk that has been studied by cognitive psychologists like Aaron Beck, Donald Meichenbaum and many others.

The unconscious aspects of personality consists of the biological drives that Freud was so interested in, but also the discarded and defended aspects of one’s self and inner experience that people do not, or in the interest of internal stability, cannot, be aware of at any particular point in time.

However, there are biological aspects of personality that human beings are quite conscious of, those described by Maslow as basic physiological needs. In addition, there are the basic non-biological human needs that motivate people, such as the need for safety and security, needs for love and belongingness, esteem, new learning, a desire for beauty, and the desire for the unfolding and development of one’s self, self-actualization.

Strictly on an internal level there is a dynamic interplay between biological needs, other basic human needs (like self-esteem for example), one’s cognitive interpretation of these needs and one’s evaluation of how to satisfy these needs. These inner dynamics are in flux, but they must come into interaction with environmental (external) factors in order to be satisfied. This is the area in which the interactionist and behavioral schools have much to contribute, as well as theories which are more internally focused.

If you look at the diagram you will see a double line between the inner person and the external world. This represents the perceptual filters we all use to interact with reality. We all process and decode external stimuli a bit differently. Insights from communication theory are useful here, as well as cognitive science, and the ideas of George Kelly in his personal construct theory. Since we encode and decode information within our own individual nuanced style, we can each be said to perceive the world with many individual differences and live in a different phenomenal world as the existentialists called it.

What this means for understanding personality is that external stimuli are always filtered through a combination of our perceptions, needs, and desires of the moment, which affect our attitudes and emotions, and our behavior toward any external event. This is why the same event is often related to so differently by different individuals, and why one stimulus that may be quite reinforcing to one person may have no reinforcing value to another.

So, human personality must be understood as an extremely complex interplay of inner forces and the outward expression of those forces as directed by the person in interaction with the environment, as the person perceives it. Certainly we can observe consistencies

in this interaction and then we tend to attribute these consistencies to concrete entities, which we usually term traits. Without a doubt trait and factor theorists have done a magnificent job of studying these consistencies and creating taxonomies of “traits.” I believe that the larger and perhaps more accurate view of the “elephant” demonstrates that anything like a “trait” is more accurately understood as a relatively habitual product of an interaction between a person’s current needs and desires, their energy level, their concept of themselves and their goals, and their perceptions of the demands (potential rewards and punishments) of their environment, all filtered through their experiences and reinforcement histories, including unconscious motivations and anxieties that may not be subject to rational analysis until they are made conscious.

So, in reality, human personality is not merely some balancing act between instinctual drives and the environment, and one’s moral scruples as Freud posited, or some pre-determined dance of genes and biological programming by the forces of evolution, or the product of some semi-mechanical schedules of reinforcement controlled from without, or the evaluative and thought oriented agencies of the mind in control of our behavior and goals, nor a collection of fixed and identifiable traits that we possess, nor some unfolding of our inner potential which will occur if we are not interfered with too much, nor are we “the relatively enduring pattern of recurrent interpersonal situations,” as Sullivan wrote.

In fact, human personality is a very complex interaction of these factors and more, so that any personality has its own patterns of adjustment both to inner forces and external ones as filtered through the unique manifestations of their personal dynamics, perceptions, needs, goals, and their attitudes toward what they know of themselves and their environment. What is common to human personality are the range of needs and the basic structures of personality, but what is unique is the organization and content of all these levels within any one individual, and the fact that they are in a dynamic flux within the individual and also in dynamic interaction with the environment. To the extent that these dynamics are in a satisfactory balance to the individual, and to requirements of the environment, the person may be said to be well adapted, even healthy. To the extent that unsatisfactory imbalances occur, the person may be said to experience dysfunctional mental states or dysfunctional behavior.

A short example may clarify this. If a person has an unsatisfactory imbalance primarily within their inner dynamics, they may be said to suffer from some type of neurotic conflict, although their external behavior may not be in any conflict with environmental demands. Another individual may not have much in the way of unsatisfactory (to the person) inner conflict, but may demonstrate behavior that is in conflict with external environmental demands. An example of this personality dynamic would be the sociopath, who harms others and violates the laws necessary for social living, but does not feel guilt or inner conflict about these actions.

The larger point is that a comprehensive, integrated understanding of personality must be capable of understanding the complex levels of human functioning both in terms of which structural aspects and levels of motivations are operating, and the content and strength of these dynamics, along with how the person interacts with the perceived environment at any particular point in time. This understanding may begin to do justice to the complexity of both the unique and common aspects of the human personality as we attempt to understand how and why people interact with themselves, their environments, and with each other. Perhaps, in time, we might even begin to see and understand the entire “elephant.”